There are several advantages to starting early:

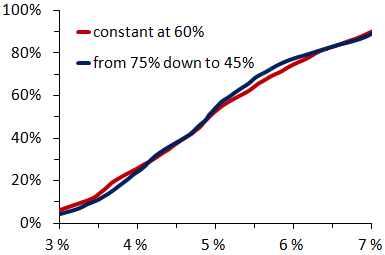

When you are decades away from retirement your main purpose should be to grow your money, so you focus on high-return asset classes. As time passes and retirement nears, you become more careful since a negative market move could rob you of money you will not have time to recover. A typical advice is to invest your age in bonds (some say age − 10): if you are 40, this means holding 60% of stocks and 40% of bonds (or 70–30). Figure 1 shows that this strategy gives results essentially indistinguishable from a static asset allocation.

Figure 1: Cumulative distribution of real annual return over thirty years: constant allocation (red) and linearly decreasing stock allocation (blue).

The outcome is about the same, the difference is that with a lower stock allocation towards the end (when your capital is greatest) means smaller losses at a time. But over the length of the investment, there is no benefit. The bond-as-age strategy is pretty much all about loss aversion.

Chances are that you will change your asset allocation (and possibly your plans) based on the performance of your portfolio. Had you invested USD5 000 every January in the S&P 500 starting in 1980 (no great feat there), you would have been a (U.S. dollar) millionaire in twenty years. In such a situation, you probably want to lock in your gains by decreasing your stock allocation (regardless of your age): you have enough money already, so your main goal is to avoid losing it.

The dashed red curve in Fig. 2 corresponds to a strategy aimed at growing $100 000 to $600 000 in thirty years. Figure 2(b) shows that the probability of having much more than $600 000 is indeed low: when the portfolio value nears $600 000 the allocation is switched to safer assets to avoid a big loss so close to the target. This active allocation yields $575 000 on average but with a median of $590 000, even higher than pure equity. (No constant asset allocation has a median higher than its average.)

The solid line in Fig. 3 shows the outcome of tuning the strategy to one's 30-year target. This active allocation can outperform a constant allocation (dashed line) by nearly 10% (around $350–400 000), and outperforms by at least 5% on the whole $230 000-to-$800 000 range. By changing one's allocation based on market moves, it is possible to quite improve the odds of reaching one's goal.

One can see in Fig. 3 that investing one's age in bonds has some success up to $350 000 but for higher values the optimal static portfolio is 100% equity and no portfolio that ends with at least 30% in bonds can compete. So this strategy is only marginally better than a static allocation at best and can be quite worse for people who want to do better than multiply their money by 3.5 over thirty years.

Note: The figure, based on the S&P 500 and US bonds for the period 1871–2014, is only intended as an indication of general trends in stocks and bonds.