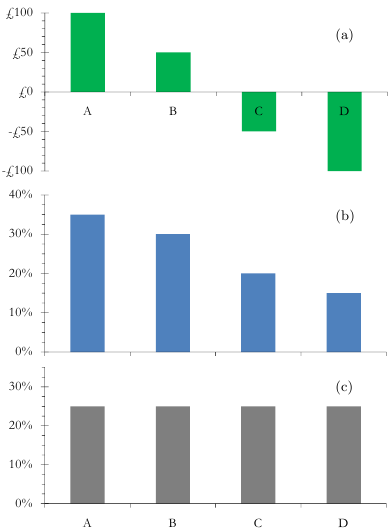

Picture the stock exchange of the tiny country of Lilliput, with only four companies, each making up one quarter of the index. Alpha Asset Management and Beta Asset Management both believe that companies A and B will outperform C and D. Beta AM therefore has the following holdings: 35% in company A, 30% in B, 20% in C and 15% in D (Fig. b). Alpha AM invests 100 lillis (£100) in A, £50 in B, and sells short £50 of C and £100 of D, as shown in Fig. a. This means that Alpha AM makes money if C and D go down, and they lose out if C and D go up in value. Figures a and b show two different ways of making essentially the same bet: A and B will do better than C and D.

Figure: Holdings of Alpha AM (a), Beta AM (b) and a tracker (c).

Assume that the managers were right: the share price of A grows by 16% and that of B by 13%, better than C (+7%) and D (+4%). The Beta fund returns 11.5% (before fees) and the index 10%. With the Alpha fund, the position on A returns £16, that on B £6.5, C loses £3.5 and D £4, for a total gain of fifteen lillis.

Gulliver invests in the Alpha fund to the point of holding (indirectly) £10 in A, £5 in B, and owing £5 of C and £10 of D. He also invests £100 in a tracker fund, which gives him twenty-five lillis in each of A, B, C and D (Fig. c). His overall portfolio is thus £35 in A, £30 in B, £20 in C and £15 in D; i.e. the same as a £100 investment in the Beta fund. But the fact that the holdings are identical does not necessarily mean that the price will be the same as well.

Beta AM charges a fee of 2.2% a year. Gulliver pays a fee of £0.2 a year for the index fund (0.2% of assets). For the fees to be the same for the same investment, the Alpha fund would have to charge £2 annually for a portfolio that earned £1.5. Even though the Alpha fund performed exceptionally well, at such a price it would lose investors' money.

The Beta fund can be seen as a low-cost tracker earning 9.8% net of fees and a fund similar to that of Alpha AM which lost 0.5% after fees. Most of the performance of active funds comes from the overall market performance, yet this accounts for only something like 10% of their fees (0.2% out of 2.2% in this example). A small fraction of the fees pays for the return and most of the fees pays for the hope of a slightly higher gain.